Moog Through the Decades

It is often the plight of the talented to labor in obscurity. Bills go unpaid, laundry goes unwashed, and demos remain ignored. Meanwhile, the genius conjures the flow state for inspiration, laboring for hours while isolated in dark rooms. And it takes a rare power to continue to labor on and hope without recognition. The best creative state necessitates being without ego and going without mainstream approval. Mounting bills, strife and infighting so often prevail while true art and innovation go unnoticed. Meanwhile, saccharine boy bands with copious hair gel, slick big-label marketing and lukewarm production reign Billboard charts.

Rarely do inventors with the foresight to span generations and decades get their due within their lifetimes. This is the case with so many virtuosos of various trades: Cymande, Brian Eno, Drexciya, Syd Barrett, Dr. Simon Warner, and especially Bob Moog.

Bob Moog left an indelible mark on musical history when he introduced handcrafted Moog Modular prototypes at the Audio Engineering Society (AES) convention in 1964. While there had been experimental production in music following WWII and the advent of the tape machine, many musicians were limited in their ability to manipulate music. The tape machine allowed non-linear editing, leading to experimentation with electronic sounds, oscillators and filters. Musicians suddenly had new tools beyond requisite strings, keys, drums and horns. This bred a small movement of experimental music making, but artists were still hindered by lack of tools—splicing a tape or playing it backwards was relatively limiting.

Bob Moog had been tinkering with sound oscillation from a young age and built his first Theremin at the age of 14. He incorporated R.A. Moog in 1953—at age 19—and sold Do-it-Yourself Theremin kits. In 1963, Bob met educator and experimental musician Herb Deutsch. The first voltage-controlled Modular synthesizer arose from their collaboration, which was unveiled at the 1964 AES convention. Bob also met musician Wendy Carlos by chance at this conference. Carlos says of that meeting, “[Moog provided] voltage-controlled oscillators, filters, envelopers, controllers — things the still-primitive world of electroacoustic music long needed.”

Wendy and Moog forged a friendship and became working partners, leading to Carlos’ triple Grammy-winning stunner Switched-On Bach, arguably the most seminal recording in the history of synthesis. The album was groundbreaking: it reinvented classical music and married what many thought was a stuffy genre with pioneering technology. When there was great compartmentalizing of music genres, Switched-On Bach bridged many divides. The album appealed to music lovers of diverse genres, converted skeptics, and went on to become the second classical album in history to go Platinum.

Moog synths quickly gained popularity with various musicians. With business success mounting, Bob was frustrated because he really just wanted to be an electric engineer and tinkerer, not a business owner. The company was sold and resold until business failures culminated with Bob recovering the legal right to use his name on his products in 2002. Moog was then divided into a profit-sharing business model where all employees are co-owners. Bob sadly passed away from a brain tumor in 2005, just three years after regaining control of his own products and use of his name therein.

Jim DeBardi works in communications for Moog and says that authenticity drives all practices there, from product conception to completion, customer service, branding and marketing. “The instruments we build are analog synthesizers. Analog is one of the most natural and physical ways to make music — you’re manipulating a raw electronic waveform. You remove the layer of electronic translation and keep the authentic signal through an analog circuit. We’re authentic at the most basic level of what we’re creating.”

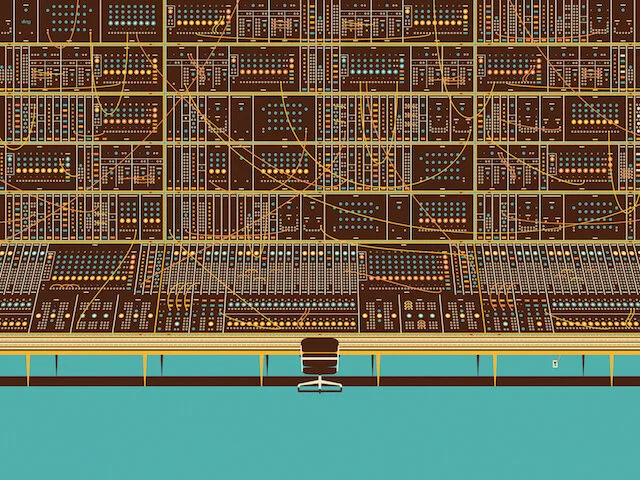

Moog debuted synthesizers at the 2015 NAMM conference that haven’t been in production for decades: the System 55, System 35 and Model 15. The Moog booth at NAMM the following year was a visual coup in fine style among a wasteland of overblown vendor presentations. Visitors were invited to experiment with modular synths nestled among thriving succulents and cacti while sitting on opulent rugs and pillows. David VanKoevering dropped in to give autographs, and a veritable petting zoo of hardware was on display.

Moog’s new modular synthesizers are exact reinventions of the originals and house the same circuits. Moog doesn’t call them “reissues” because the production process was so precise and intensive — these are as close to original as possible. They boast hand-soldered circuit boards and handcrafted wire harnesses and circuit placements. DeBardi says, “Parts made 50 years ago were made on a different machine, with different geography. All of these factors have an effect on the final product, so we sourced ‘new old’ stock components and parts built in the ’60s and ’70s that were overstock or put away.”

While Moog may have never been awarded the recognition he was due in his lifetime, his legacy lives on, as do his values. “Moog was a boundary shifter, prepared to let the culture help shape his instrument … in the end, he was more of a ’60s guy than anyone ever realized,” writes Trevor Pinch in Analog Days: The Invention And Impact Of The Moog Synthesizer. Bob knew he was making tools for artists and constantly worked with artists to understand their needs. Moog wanted nothing of the spotlight — just to engineer tools to exponentially expand an artist’s repertoire.

This article was written for American Songwriter. Thanks to Caine O’Rear, Jim DeBardi, Orqid, Patchwerks, and Jaan Uhelszki of Relix Magazine / Creem Magazine for their contributions to this article.

This graphic is part of an awesome series by DKNG Studios benefiting Bob Moog Foundation.