Don't Shoot, We're Devo: Part II

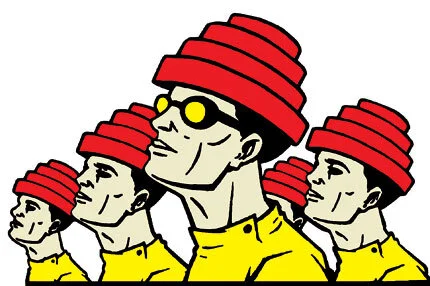

Even today, some 40 years after the band’s debut, there are legions of Devo-tees. Perhaps it’s due to the philosophy of De-evolution and the precocious employ of musical, visual and philosophical elements before it was in vogue. Perhaps it’s an inevitable outcome of years spent releasing daring records bound to off-the-wall antics, to court popularity and success while simultaneously shunning it. Perhaps it’s just the magnetism of the yellow-jumpsuit-”energy-dome” combination.

Whatever the allure, for every fan of the MTV-happy “Whip It” there’s another cataloging Devo t-shirts in cellophane wrap organized by concert year and sub-categorized by month and color. Earplug’s Sara Jayne Crow met with Gerald Casale of Devo over the course of several months. The following is the second installment in a series covering the De-evolution philosophy, Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies,” and the “rogue’s gallery” of Devo history.

Sara Jayne Crow: How’s Los Angeles?

Gerald Casale: Everybody’s doing meaningless shit, and they just do it in this endless procession of consumption. It’s like taking a shit. Out here [in LA], it’s just sadistic. The girls are really entitled, aggressive and mean. They’ve turned into the ways guys used to be… callow and womanizing. The girls are laughing at the guys who care about them. It’s just mind-boggling.

SC: Isn’t that just in keeping with the patterns of history, though? The pendulum swings?

GC: Yeah, but none of it’s good.

SC: Has it ever been?

GC: Maybe not. I guess I’ve never seen the volume of bad be so high and up-front, that’s all. I’ve never seen so many stupid people.

SC: De-evolution at work?

GC: Yes. So many stupid people who are kind of proud of being stupid. Shameless. They don’t even feel stupid at all. It’s like how we got to a point in America where you can be put down as a politician if you were able to speak as if you knew more than the crowd you were talking to.

SC: Let’s talk about the beginnings of Devo and philosophy, which was couched in the concept of de-evolution. You have spoken of the band forming as a reaction to the brute military force at the Kent State University antiwar protest in 1970 in an older Vermont Review interview.

GC: Yes. I think I was kind of a hippie until that point. I believed naively that there was justice, that good deeds mattered, and that there really was a democracy enforcing the Constitution, and that bigotry and segregation were aberrations, not the norm. And I was wrong. The evil far outweighs the good, and you would have to be a constant warrior vigilante, day and night, to make a dent in it. One of the things I could do was to have an artistic aesthetic that was a sort of gun in your face, giving some back to ‘em, but in a way that you’re allowed to operate. Because if I’d done what I really felt like doing, I’d be in jail for homicide.

SC: What did you really feel like doing, or who did you really feel should be killed?

GC: Oh, there were so many people that should have died.

SC: Nixon?

GC: Sure, sure, absolutely. There were so many, locally and nationally. But it’s like the Medusa. It seems to work when the right wing kills off a visionary leader because somebody trying to give people hope and a sense of direction and lift them up really is important. But there is always another evil guy. There’s an endless supply of those guys. Evil is easy; it’s based on fear and hopelessness. But the opposite isn’t easy. You change history by killing a visionary. The evil goes from the top to the bottom and right down from the largest kind of implications for masses of people on a political level to interpersonal relationships, love and business relationships. I have not been able to put what I know into practice, in terms of me becoming cynical enough to act differently. I always act as if things could turn out well, or as if what you put into something matters.

SC: So what are you working on right now, aside from the new album?

GC: I’m working on a first draft of the early days of Devo movie with Matt Diehl, a writer for Rolling Stone. It’s about Devo in the sad, sad Akron days beginning in 1974. It shows the truth, which is stranger than fiction, where, against all odds, and totally whacked-out, this art band goes from being this hopeless joke everyone laughs.. to synching up with the new wave and punk movements… It goes all the way through to where we get signed and try to start our first tour and get the deal to go on Saturday Night Live. The movie ends there, although there’s a coda or postscript that takes place in 1980 when “Whip It” is a hit, and everyone wants us to write another hit and meet with producers. There’s also a prequel including the killings at Kent State. It’s the probable journey and struggle to success, but the success is a question mark.

SC: How did you choose that particular time period?

GC: Because that’s where the important formation of the whole concept turning into a productive reality took place, against all odds and with a lot of conflict and dark humor, and where all the revolutionary aesthetic that we had got created, including our first 10-minute film, The Truth About De-evolution. You’re seeing this rogue’s gallery of people, the record company executives and New York promoters, and Iggy Pop, David Bowie, Brian Eno, Dean Stockwell, Neil Young and Toni Basil, Richard Branson, Ron Blakely… and it’s insane, how it all works.

SC: How did you treat the Brian Eno part?

GC: Just truthfully. It was pretty strange. Brian Eno and Devo were on two different dimensional planes that kind of intersected, but not really.

SC: Did you talk about the “Oblique Strategies” [Eno's approach to finding a new formula for the Devo sound]?

GC: Oh, yeah.

SC: What did you make of that?

GC: Devo being the smartass intellectuals that we were, we thought the Oblique Strategies were pretty wanky. They were too Zen for us. We thought that precious, pseudo-mystical, elliptical stuff was too groovy. We were into brute, nasty realism and industrial-strength sounds and beats. We didn’t want pretty. Brian was trying to add beauty to our music.

SC: He probably wanted something spontaneous for your sound.

GC: We knew so much what we wanted. What his ideas were usually were antithetical to what we needed to do. The songs we brought into that studio we had played and played and played. We were married to what they were. We were driven by anger.

SC: Yes, and that anger seems to have drove you through three decades. What you were doing thirty years ago is more timely now than it ever has been.

GC: Yeah, but we knew then we were doing something that had nothing to do with trends. We were just trying to perfect what we did, and people made fun of us, saying, “Why the fuck are you doing this? Who wants to hear this, and why are you trying so hard?” It was because we had an idea. And now our music sounds contemporary.

SC: Now people are trying to re-make that punk, retro synth sound Devo mastered.

GC: There was a generation of kids that never heard us and finally found us and got inspired. And they don’t want grunge. They don’t want to hear about some whining bastard’s personal pain. They want something that unifies a group of people, inspires them, and lifts them up. And that is exactly what is new about new wave. That’s exactly what new wave did. When you heard God Save the Queen, and you were me at my age, and you heard The Clash’s London Calling, it was incredible. It made you feel like you could move, like you could go forward. It brought people together, and lifted them up. I think people need that now.

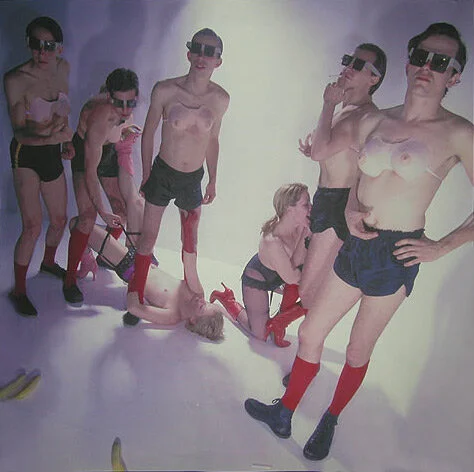

Photo credit © Moishe Brakha

This article is part of a series originally published in Flavorwire.